To prepare aluminum for anodizing, the surface is first thoroughly cleaned and rinsed, and then placed into a bath of some electrolytic solution like sulfuric acid. An electrolyte is an electrically conductive solution with lots of positive and negative ions that it wants to swap.

A positive electric charge is applied to the aluminum, making it the “anode”, while a negative charge is applied to plates suspended in the electrolyte. The electric current in this circuit causes positive ions to be attracted to the negative plates, and negative ions to flock to the positive anode, the piece of aluminum.

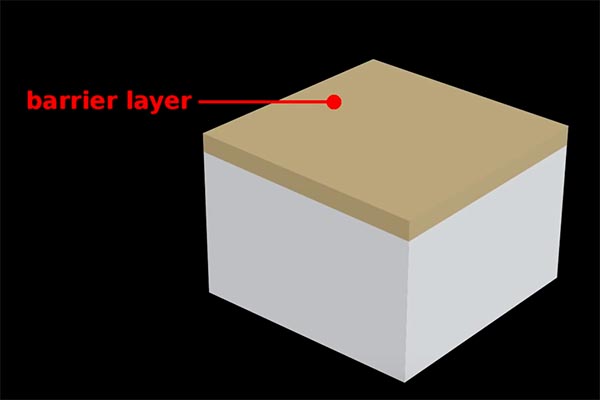

The electrochemical reaction causes pores to form on the surface of the aluminum as excess positive ions escape. These pores form a geometrically regular pattern and begin to erode down into the substrate. The aluminum at the surface combines with the negatively charged O2 ions to create aluminum oxide. This is called a barrier layer, a defense against further chemical reactions at those spots.

The barrier layer protects against further oxidation at the surface

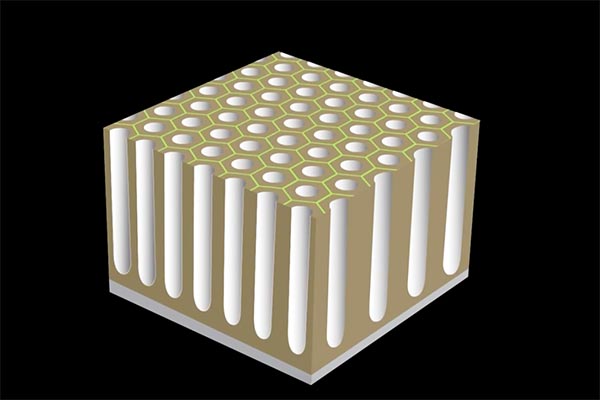

As current continues to be applied, the relatively weak and reactive areas of the pores will continue to penetrate deeper into the substrate, forming a series of column-like hollow structures.

A regular pattern of surface porosity is created when electric current is applied.

The longer the current is applied the greater the penetration of these columns. For typical non-hard coatings, the depth can be up to 10 microns. Once this level is reached, and if no color is needed, the process is stopped and the surface can be sealed simply by rinsing in water. That will leave you with a hard, natural aluminum oxide coating, able to withstand chemical attack and very scratch resistant. Aluminum oxide is rated 9 out of 10 on the Mohs hardness scale, meaning second only to diamond.

Hard anodizing, sometimes called Type III, offers greater corrosion protection and resistance to wear in extreme environments or with moving mechanical parts subject to a lot of friction. This is produced by continuing the electrical current until the depth of the pores exceeds 10 microns, all the way to 25 microns or even more. This takes more time and is more expensive but produces a superior result.

Although aluminum doesn’t rust, it can deteriorate in the presence of oxygen, which is called oxidation. What is oxidation? It simply means to react with oxygen. And oxygen is very reactive, readily forming compounds with most other elements. When aluminum is exposed to the atmosphere it quickly forms a layer of aluminum oxide on the surface, and this layer provides a degree of protection against further corrosion.

Anodizing is functional and beautiful

But aluminum must withstand more than just pure air and water. Acid rain, salt water and other contaminants can still exploit weaknesses in the surface passivation. Even modern alloys will vary in response to this environmental exposure, ranging from mere surface discoloration all the way to mechanical failure.

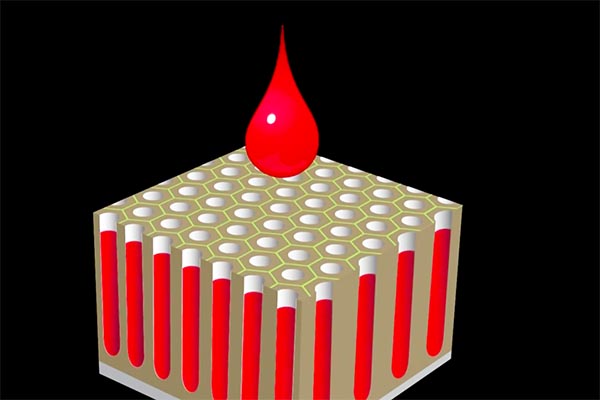

Colored aluminum is what most of us picture when we think of anodizing. That’s the real genius of this process. The nice, stable pores etched into the surface are ideal for introducing tints or pigments.

Empty pores are ideal for adding colorants.

The pigment fills all the empty pores up to the surface, where it’s then permanently sealed off. That’s why anodized colors are so durable – they can’t be scratched off from the surface because in fact the colors are deep down and can only be removed by grinding away the substrate.

After coloring, anodized aluminum has a characteristic “metallic” look. This is caused by two factors. One, because of the uniform electro-chemical etching, a rough surface is left behind. The deeper the pores, the rougher the surface will be but the colors will also be that much more durable.

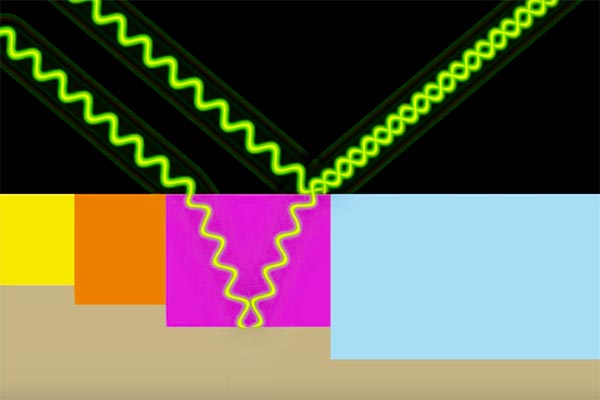

Secondly, light striking the surface partly interacts with the colorant and partly with the uncolored metal at the top.

Light changes colors as it reflects from an anodized surface.

So the light that bounces back to strike your eye will in fact be a combination of two distinct wavelengths interacting as they reflect from slightly different surfaces. This causes the distinctive shine of aluminum anodizing.

Yes. Anodizing also works with magnesium, titanium and even conductive plastics. It’s inexpensive, reliable and eminently durable. That’s why it’s so commonly used in architectural fittings, because it’s both beautiful and almost impervious to the effects of weathering.

Anodizing requires that a part is immersed in a series of chemical baths. Holding a part in position requires that it be mounted on a hanger of some kind to keep it from falling to the bottom of the tank. Wherever the holding fixture touches the part, that area will be blocked and the anodizing chemicals won’t work properly. That’s why it’s smart to design a place on your part which can be used for holding but which won’t be adversely affected cosmetically.

When you contact us for a free quotation and project review, we’ll be able to offer advice on the many different finishing services that we offer for rapid protoypes and low-volume manufacturing. Our specialists will help you to find the solution that fits your budget, time to market and desired results. Let’s get started today!