Machine screw threads, along with many other kinds of threaded fittings, are used around us every day in millions of applications. In fact, they’re so ubiquitous that they largely go unnoticed by most of us, and to the inexperienced eye they all look and perform pretty much the same.

In fact, screw threads are surprisingly diverse and complex mechanisms that took a very long time to develop, and they still haven’t been perfected yet. There are in fact so many types and so many applications that engineers need to understand the structure and terminology of screw threads so they can effectively communicate with their manufacturing partners to get exactly the results they need.

Basic screw forms were known to the early Greek natural philosophers from as early as the 4th century B.C. For a thousand years, threaded shafts were used in wine and oil presses, while Archimedes’ screws are still used today to raise water.

However, it wasn’t until the 14th century that hand-made threads and screws were used they way we do now, to hold two or more things together under mechanical tension and compression.

200 year old hand-made screw

During the Industrial Revolution more mechanical objects were being bolted and screwed together than ever before. These early nuts, bolts and screws were made either with hand files or using simple lathes, and they had no common standards between industries or even separate companies. Myriad different types appeared everywhere – on boilers and steam fittings, locomotives and ships, armaments or printing presses – and none of them were interchangeable.

It eventually took many years and lots of trial and error to figure out what type of threads worked best for which applications and then to establish both national and international standards based on these types.

At Star Rapid we usually work with either ASME threads – used in North America and sometimes called Imperial – and metric or ISO threads, used pretty much everywhere else. For either system it’s essential that an engineer understands the terminology associated with it and how to specify it in a CAD file or engineering drawing.

What’s the difference between a bolt and a screw? A bolt passes through the pieces to be joined and holds them together under compression using a nut on the threaded shaft. Because of this arrangement, bolts are chiefly used for resisting lateral or side-loading. Screws, however, engage with a mating thread in the material and apply a holding force inline with the shaft of the screw.

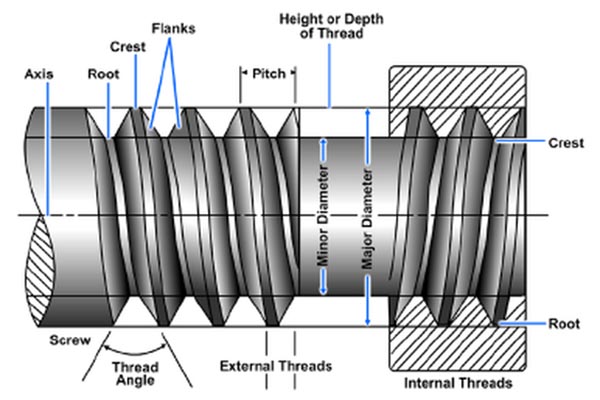

Here are Star Rapid we use CNC machining to create threaded features on components of all types, so we know it’s essential that male and female threads are a perfect match. That’s why engineers and product developers need to use the following terms when they are communicating with the manufacturer.

Crest: High point of the groove

Root: Low point of the groove

Thread Angle: Angle between opposing flanks

Major diameter: Largest diameter

Minor diameter: Smallest diameter

Pitch: Distance between crests. For imperial threads, this is often stated as threads per inch or TPI

Pitch Line: This is an imaginary line, running parallel to the centerline of the screw, lying halfway between the high and low projected intersections of the angled flanks

Pitch Diameter: Measured from pitch-line to pitch-line on opposite sides of the thread

Most standards have some version of fine, medium and coarse threads for different applications

Fine threads are typically found in smaller diameters and on precision instruments where it’s necessary to make small adjustments for alignment. The drawback however is that they’re more easily cross-threaded, stripped, or galled. Galling happens when the mating threads get partially crushed together.

Galling can be prevented with lubrication or an oxide coating. Sometimes threaded inserts, like HeliCoils, are used to put a harder thread inside of a softer surrounding base material.

Medium threads are the most common for general-purpose assemblies, while coarse threads are the easiest to make. They have the most resistance to pull-out and are often found on very heavy industrial machinery. Coarse threads also have the most clearance between threads for a plating or coating that may be applied later.

External threads are made with a lathe or by thread rolling. Thread rolling doesn’t waste material and it can improve the strength of threads because it compresses the stock material rather than shearing it.

Thread roller, courtesy of Tesker.com

Internal threads are made by drilling and tapping, which used to be separate operations. But there are now hybrid cutting tools that can drill and tap in a single operation, saving both time and money.

In all of the above cases, product developers should specify if they have a particular method that they prefer. Otherwise the manufacturer will use the method that is fastest while still meeting the product’s specifications.

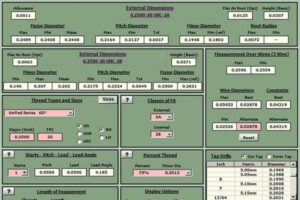

Main page of ME ThreadPal

Because there are so many different types of thread standards there’s a great risk of inaccuracy and potential error in communication between a vowin.cn' target='_blank'>product designer and their manufacturing partner when specifying threaded features. To avoid these errors, we strongly recommend using a thread calculating tool such as ME ThreadPal, ThreadTech or something similar.

They work with all major standards and provide the information that a machinist needs to make your threads correctly the first time.