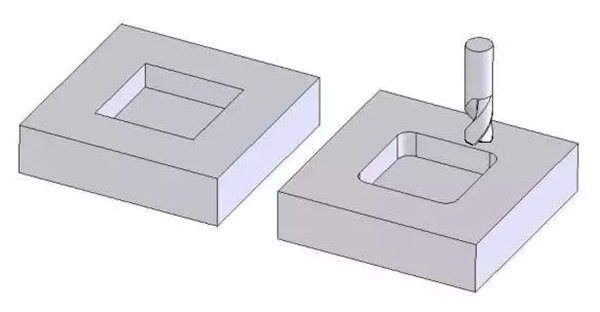

These conflicting requirements do not create a deadlock, however. Engineers and machinists have come up with numerous design maneuvers to deal with this issue.

Change the Corners to Fillets

The simplest, most obvious solution is to avoid sharp inside corners altogether. Granted, this may not look like a ‘solution’ to the problem at hand, but this is what experts recommend across the board. Most designs are flexible to change in corner radius, with small adjustments getting the job done while maintaining the same functionality.

The main reason for this recommendation is its simplicity. The corner machining techniques we will discuss later all require extra effort, cost, and time. If there is a way of avoiding these, prioritize it.

The other reason is process stability. Cutting tools like endmills are not suitable for machining very deep pockets. The generally recommended maximum depth of cut is four times the tool’s diameter. Beyond these limits, problems like chatter, tool breakage, and poor surface finish begin to appear. All of these hinder the cutting tool’s capability to produce high-quality sharp inside corners.

Thus, when designers choose to convert corners to fillets, they should also pay attention to the fillet radius. Depending on how deep the pocket is, they should select an appropriate corner radius that the production department can safely machine and also preserves the functionality of the part.

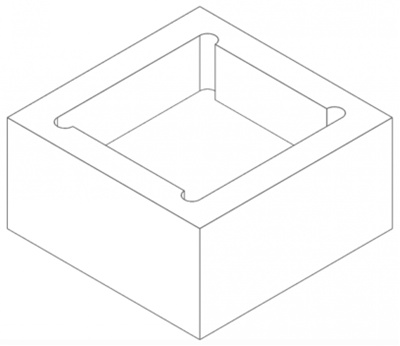

T-bone and Dogbone Fillets

Another solution is to add undercuts at each sharp corner. An undercut is a machining feature where the cut extends into the corner beyond the periphery of the internal pocket. In other words, it removes extra material from the corners.

This works best when you need sharp inside corners to fit an external component inside the internal pocket. It does not affect the functionality or performance of the assembly and still makes way for the mating component to fit in. Moreover, it might lead to some useful weight reduction.

There are two popular solutions that machinists regularly use for sharp corners in machining.

T-bone

The simpler, easier type of corner undercut is the ‘T-Bone’. In this operation, the cutter moves into the corner in just one direction. Typically, the extension of the cut is at least half the diameter of the cutter to make adequate space for the mating objects to fit together.

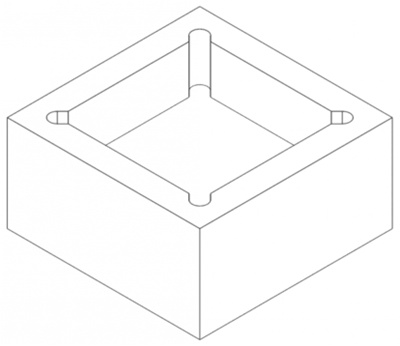

Dog Bone

The other type of undercut is the ‘dog bone’, taking its name from its resemblance to the shape of a dog bone. It is different from T-bones as it extends the cut in two directions instead of just one. This kind of undercut is slightly more complex to machine, but it is aesthetically pleasing.

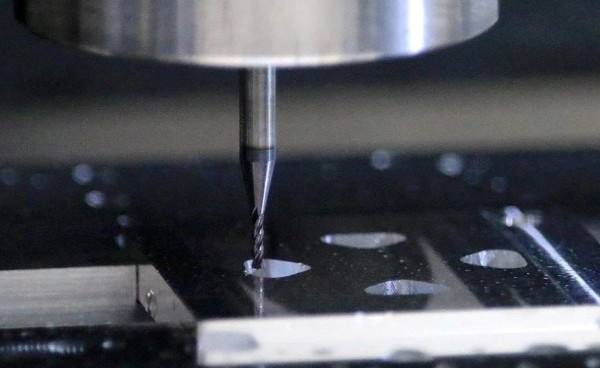

Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM)

Now, let us digress a bit and look at solutions slightly outside the classic machining territory. EDM is a popular manufacturing process that uses electric sparks between the workpiece and tool to remove material through melting and erosion. It has special applications in the machining of inside corners. We will discuss two types of EDM processes: die-sink EDM and wire EDM.

Die-Sink EDM

In a die-sink EDM process, the cutting tool is a custom-designed die that is gradually lowered (sunk) into the workpiece. Since the die is the negative form of the feature geometry, it is an external component. Thus, it can have sharp corners without any issues.

Wire EDM

Wire EDM is different from die-sink EDM. Its tool is a thin wire that moves along the contours of the feature to cut material. It is highly suitable for machining sharp corners due to its incredibly small tool size of less than 0.1 mm in diameter. This means that wire EDM can produce inside corners with a radius of as small as 0.05 mm, which is ‘sharp’ by all means.

There are downsides to the EDM process though. Generally, EDM is much slower than conventional machining and manufacturers must have a solid reason to justify its usage for corner machining. Moreover, EDM can be tricky to plan out for machinists due to its complexity. Furthermore, it is limited to only electrically conductive materials and has a poor surface finish which may require further processing to get it up to the mark.

Manual Cutting

Finally, when machines fail in producing a high-quality sharp corner, manual skills come in handy. The last resort is to utilize various hand tools to cut, grind, and polish the internal corner to achieve the desired shape.

Some common hand tools include chisels, files, and sandpapers. Understandably, manual processes are time-consuming and certainly not as accurate as machines. However, when using machines is not feasible, they are a good alternative.